The Technology of Liberalism

In every technological revolution, we face a choice: build for freedom or watch as others build for control.

-Brendan McCord

There are two moral frames that explain modern moral advances: utilitarianism and liberalism.

Utilitarianism says: “the greatest good for the greatest number”. It says we should maximize welfare, whatever that takes.

Liberalism says: “to each their own sphere of freedom”. We should grant everyone some boundary that others can’t violate, for example over their physical bodies and their property, and then let whatever happen as long as those boundaries aren’t violated.

(Before the philosophers show up and cancel me: “utilitarianism” and “liberalism” here are labels for two views, that correspond somewhat but not exactly to the normal uses of the phrases. The particular axis I talk about comes from my reading of Joe Carlsmith, who I’ll quote at length later in this post. Also, for the Americans: “liberalism” is not a synonym for “left-wing”.)

Some of the great moral advances of modernity are:

women’s rights

abolition of slavery

equality before the law for all citizens of a country

war as an aberration to be avoided, rather than an “extension of politics by other means”

gay rights

the increasing salience of animal welfare

Every one of these can be seen as either a fundamentally utilitarian or fundamentally liberal project. For example, viewing wars of aggression as bad is both good for welfare (fewer people dying horrible deaths way too early), and a straightforward consequence of believing that “your right to swing your fist ends where my nose begins” (either on a personal or national level). Women’s rights are both good for welfare through everything from directly reducing gender-based violence to knock-on effects on economic growth, as well as a straightforward application of the idea that people should be equal in the eyes of the law and free to make their own choices and set their own boundaries.

Utilitarian aims are a consequence of liberal aims. If you give everyone their boundaries, their protection from violence, and their God and/or government -granted property rights, then Adam Smith and positive-sum trade and various other deities step in and ensure that welfare is maximized (at least if you’re willing to grant a list of assumptions). More intuitively and generally, everyone naturally tries to achieve what they want, and when you ban boundary-violating events, everyone will be forced to achieve what they want through win-win cooperation rather than, say, violence.

Liberal aims are a consequence of utilitarian aims. If you want to maximize utility, then Hayek and the political scientists and the moral arc of humanity over the last two centuries all show up and demand that you let people choose for themselves, and have their own boundaries and rights. Isn’t it more efficient when people can make decisions based on the local information they have? How many giga-utils have come from women being able to pursue whatever job they want, or gay people being free from persecution? Hasn’t the wealth of developed countries, and all the welfare that derives from that, come from institutions that ensure freedom and equality before the law, enforce a stable set of rules, and avoid arbitrary despotism?

Much discussion of utilitarianism focuses on things like trolley problems that force you to pick between welfare losses and boundary violations. Unless you happen to live near a trolley track frequented by rogue experimental philosophers, however, you’ll notice that such circumstances basically never happen (if you are philosophically astute, you’ll also be aware that as a real-life human you shouldn’t violate the boundaries even if it seems like a good idea).

However, as with everything else, the tails come apart when things get extreme enough. The concept of good highlighted by welfare and that highlighted by freedom do diverge in the limit. But will we get pushed onto extreme philosophical terrain in the real world, though? I believe we don’t need to worry about a sudden influx of rogue experimental philosophers, or a trolley track construction spree. But we might need to worry about the god-like AI that every major AGI lab leader, the prediction markets, and the anonymous internet folk who keep turning out annoyingly right about everything warn us might be coming in a few years.

The Effective Altruists, to their strong credit, have taken the intersection of AI and moral philosophy seriously for years. However, their main approach has been to perfect alignment—the ability to reliably point an AI at a goal—while also in tandem figuring out the correct moral philosophy to then align the AI to, such that we point it at the right thing. Not surprisingly, there are some unresolved debates around the second bit. (Also, to a first approximation, the realities of incentives mean that the values that get encoded into the AI will be what AI lab leadership wants modulo whatever changes are forced on them by customers or governments, rather than what the academics cook up as ideal.)

In this post, I do not set out to solve moral philosophy. In fact, I don’t think “solve moral philosophy” is a thing you can (or should) do. Instead, my concern is that near-future technology by default, and AI in particular, may differentially accelerate utilitarian over liberal goals. My hope is that differential technological development—speeding up some technologies over others—can fix this imbalance, and help continue moral progress towards a world that is good by many lights, rather than just one.

The real Clippy is the friends we made along the way

Joe Carlsmith has an excellent essay series on “Otherness and control in the age of AGI“. It’s philosophy about vibes, but done well, and thoroughly human to the core.

He starts off with a reminder: Eliezer Yudkowsky thinks we are all going to die. We don’t know how to make the AIs precisely care about human values, the AI capabilities will shoot up without a corresponding increase in their caring about our values, and they will devour the world. A common thought experiment is the paperclip-maximizer AI, sometimes named “Clippy” after the much-parodied Microsoft Office feature. The point of the thought experiment is that optimizing hard for anything (e.g. paperclips) entails taking over the universe and filling it with that thing, and in the process destroy everything else. In his essay “Being nicer than Clippy”, Carlsmith writes:

Indeed, in many respects, Yudkowsky’s AI nightmare is precisely the nightmare of all-boundaries-eroded. The nano-bots eat through every wall, and soon, everywhere, a single pattern prevails. After all: what makes a boundary bind? In Yudkowsky’s world (is he wrong?), only two things: hard power, and ethics. But the AIs will get all the hard power, and have none of the ethics. So no walls will stand in their way.

The reason the AIs will be such paperclipping maximizers is because Yudkowsky’s philosophy emphasizes some math that points towards: “If you aren’t running around in circles or stepping on your own feet or wantonly giving up things you say you want, we can see your behavior as corresponding to [expected utility maximization]” (source). Based on this, the Yudkowskian school thinks that the only way out is very precisely encoding the right set of terminal values into the AI. This, in turn, is harder than teaching the AIs to be smart overall because: “There’s something like a single answer, or a single bucket of answers, for questions like ‘What’s the environment really like?’ [... and so w]hen you have a wrong belief, reality hits back at your wrong prediction [...] In contrast, when it comes to a choice of utility function, there are unbounded degrees of freedom”.

So: anything smart enough is a rocket aimed at some totalizing arrangement of all matter in the universe. You need to aim the rocket at exactly the right target because otherwise it flies off into some unrelated voids of space and you lose everything.

To be clear, to Yudkowsky this is a factual prediction about the behavior of things that are smart enough, rather than a normative statement that the correct morality is utilitarian in this way. Big—and very inconvenient—if true.

Now at this point you might remember that even some humans disagree with each other about what utopia should look like. Of course, a standard take in AI safety is that the main technical problem we face is pointing the AIs reliably at anything at all, and therefore arguing over the “monkey politics” (as Carlsmith puts it) is pointless politicking that detracts from humanity’s technical challenge.

However, in another essay in his sequence, Carlsmith points out that any size of value difference between two agents could lead to one being a paperclipper by the lights of the other:

What force staves off extremal Goodhart in the human-human case, but not in the AI-human one? For example: what prevents the classical utilitarians from splitting, on reflection, into tons of slightly-different variants, each of whom use a slightly-different conception of optimal pleasure (hedonium-1, hedonium-2, etc)? And wouldn’t they, then, be paperclippers to each other, what with their slightly-mutated conceptions of perfect happiness?

This is not just true between agents, but also between you at a certain time and you at a slightly later time:

[..] if you read a book, or watch a documentary, or fall in love, or get some kind of indigestion [...] your heart is never exactly the same ever again, and not because of Reason [...so] then the only possible vector of non-trivial long-term value in this bleak and godless lightcone has been snuffed out?! Wait, OK, I have a plan: this precise person-moment needs to become dictator. It’s rough, but it’s the only way. Do you have the nano-bots ready? Oh wait, too late. (OK, how about now? Dammit: doom again.)

Now, this isn’t Yudkowsky’s view. But why not? Remember: in the Yudkowskian frame, for any agent to “want” something coherently, it must have a totalizing vision of how to structure the entire universe. And who is to say that even small differences in values don’t lead to different ideal universes, especially under over-optimization to the limit of those values? After all, as Yudkowsky repeatedly emphasizes, value is fragile. However, the overall framework, Carlsmith argues, creates an overall “momentum towards deeming more and more agents (and agent-moments) paperclippers”. It makes it very natural that we’ve just got to know exactly what is valuable well enough to write it down in a form without contradictions that we can optimize ruthlessly without breaking it. And we should do this as soon as possible, because our values might change, or because another entity might get to do it first, and chances are they’d be a paperclipper with respect to us. Time to take over the universe, for the greater good!

What’s the alternative? In the original Carlsmith essay, he writes:

Liberalism does not ask that agents sharing a civilization be “aligned” with each other in the sense at stake in “optimizing for the same utility function.” Rather, it asks something more minimal, and more compatible with disagreement and diversity – namely, that these agents respect certain sorts of boundaries; that they agree to transact on certain sorts of cooperative and mutually-beneficial terms; that they give each other certain kinds of space, freedom, and dignity. Or as a crude and distorting summary: that they be a certain kind of nice. Obviously, not all agents are up for this – and if they try to mess it up, then liberalism will, indeed, need hard power to defend itself. But if we seek a vision of a future that avoids Yudkowsky’s nightmare, I think the sort of pluralism and tolerance at the core of liberalism will often be more a promising guide than “getting the utility function that steers the future right.”

So, then: we have Yudkowsky, claiming that, as much as we humans benefit from centering rights and virtues in our idea of the good, the AIs will be superhumanly intelligent, and it is the nature of rationality that beings bend more and more towards a specific type of “coherence”—and hence utilitarian consequentialism—as they get smarter.

So, this then is the irony: Yudkowsky is a deep believer in humanism and liberalism. But his philosophical framework makes him think anything sufficiently smart becomes a totalizing power-grabber. The Yudkowskian paperclipper nightmare explicitly comes from a lack of liberalism, in the rules-and-boundaries sense. Yudkowsky’s ideal solution would be to figure out how to encode the non-utilitarian limits into the AI—”corrigibility”, for example, means that the AI doesn’t resist being corrected, and is something where Yudkowsky and others have spent lots of time on trying to make it make sense within the expected-utility-maximising paradigm. But that seems deeply technically difficult within the expected-utility-maximizer paradigm.

These philosophical vibes, plus the unnaturalness of non-consequentialist principles given a framework that makes non-consequentialism deeply unnatural, has given the AI safety space an ethos where the only admissible solution is getting better at fiddling with the values that are going into an AI, and then fiddling with those values. The AI is a rocket shooting towards expected utility maximization, and if it hits even slightly off, it’s all over—so let’s aim the rocket very precisely! Let’s make sure we can steer it! Let’s debate whether the rocket should land here or there. But if the threat we care about is the all-consuming boundary violations ... maybe we shouldn’t build a rocket? Maybe we should build something less totalizing. Maybe we shouldn’t try to reconfigure all matter in the universe—”tile the universe”—into some perfectly optimal end-state. Ideally, we’d just boost the capabilities of humans who engage with each other under a liberal, rule-of-law world order.

The point Yudkowsky fundamentally makes, after all, is that you shouldn’t “grab the poison banana”; that hardcore utility-maximization is very inconvenient if you want anything or anyone to survive—or if you think that there’s the slightest chance you’re wrong about your utility function.

There’s also a more cynical way to read the focus on values over constraints in AI discourse. If you build the machine-god, you will gain enormous power, and can reshape the world by your own lights. If you think you might be in the winning faction in the AI race, you want to downplay the role of constraints and boundaries, and instead draw the debate towards which exact set of values should be prioritized. This tilts your faction’s thinking a bit towards yours, while increasing the odds that your faction is not constrained. If you’re an AI lab CEO, how much better is it for you that people are debating what the AI should be set to maximizing, or whether it should be woke or unwoke, rather than how the AI should be constrained or how we should make sure it doesn’t break the social contract that keeps governments aligned or permanently entrench the ruling class in a way that stunts social & moral progress?

Of course, I believe that most who talk about AI values are voicing genuine moral concerns rather than playing power games, especially since the discourse really does lean towards the utilitarian over the liberal side, and since the people who (currently) most worry about extreme AI scenarios often have a consequentialist bent to their moral philosophy.

But even in the genuineness there’s a threat. Voicing support for simple, totalizing moral opinions is a status signal among the tech elite, perhaps derived from the bullet-biting literal-mindedness that is genuinely so useful in STEM. The e/accs loudly proclaim their willingness to obey the “thermodynamic will of the universe”. This demonstrates their loyalty to the cause (meme?) and their belief in techno-capital (and, conveniently, willingness to politically align with the rich VCs whose backing they seek). What about their transparent happiness for the techno-capital singularity to rip through the world and potentially create a world without anyone left to enjoy it? It’s worth it, because thermodynamics! Meanwhile, among the AI safety crowd, it’s a status signal to know all the arguments about coherence and consequentialism inside out, and to be willing to bite the bullets that these imply. But sometimes, that there is no short argument against something means not that it is correct, but rather that the counter-argument is subtle, or outside the paradigm.

The limits and lights of liberalism

I’m worried of leaving an impression that liberalism, boundaries, and niceness are an obvious and complete moral system, and utilitarianism is this weird thing that leads to paperclips. But like utilitarianism, liberalism breaks when taken to an extreme.

First, it’s hard to pin down what it means. Carlsmith writes:

[A]n even-remotely-sophisticated ethics of “boundaries” requires engaging with a ton of extremely gnarly and ambiguous stuff. When, exactly, does something become “someone’s”? Do wild animals, for example, have rights to their “territory”? See all of the philosophy of property for just a start on the problems. And aspirations to be “nice” to agents-with-different-values clearly need ways of balancing the preferences of different agents of this kind – e.g., maybe you don’t steal Clippy’s resources to make fun-onium; but can you tax the rich paperclippers to give resources to the multitudes of poor staple-maximizers? Indeed, remind me your story about the ethics of taxation in general?

Second, there are things we may want to ban or at least discourage, even if doing so means interventionism. Today we (mostly) think that a genocide warrants an international response, that you should catch the person jumping off the building to kill themself, and that various forms of paternalism are warranted, especially towards children. In the future, presumably there are things people could do that are bad enough by our lights that we think we can’t morally tolerate that in our universe.

Third, the moral implications of boundaries and rights change with technology. For example, today cryptocurrency might be helpful for people in unstable low-income countries, but tomorrow scheming AI systems might take advantage of the existence of a decentralized, uncontrollable payments rail to bribe, blackmail, and manipulate in ways we wish we hadn’t given them the affordances to do. Today we might be completely fine giving everyone huge amounts of compute that they have full control over, but tomorrow it might be possible to simulate digital minds and suddenly we want to make sure no one is torturing simulated people. Historically, too, it’s worth noting that while almost every place and time would’ve benefited from more liberalism and rule-of-law, sometimes it’s important that there are carefully-guarded mechanisms to tinker with those foundations. What set British institutions apart in the 18th and 19th centuries was not just that they were more laissez-faire and gave better rights than other countries of the age, but also that they were able to adapt in times of need. In the US, FDR’s reforms required heavy-handed intervention and the forcing through of major changes in government, but were (eventually) successful at dragging the country out of recession. Locking in inviolable rights is a type of lock-in too.

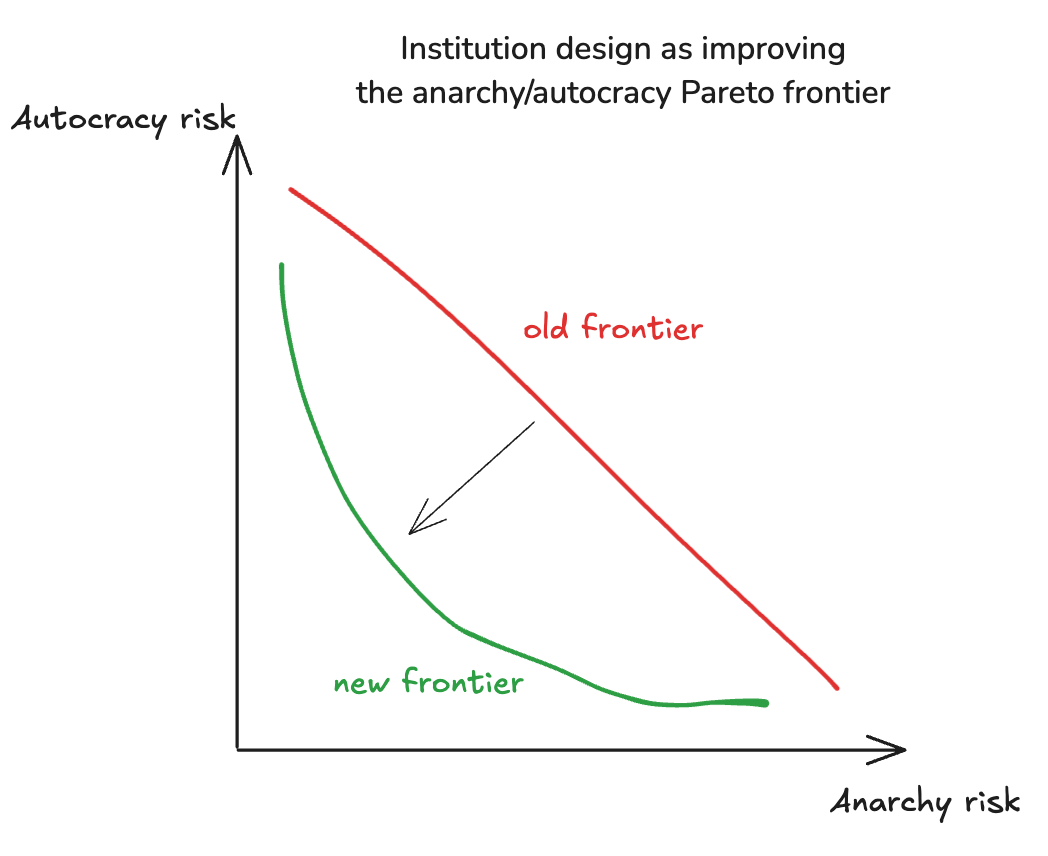

Fourthly, liberalism has a built-in tension between a decentralizing impulse and a centralizing impulse. The decentralization comes from the fact that the whole point is that everyone is free. The centralization comes from things like needing a government with a monopoly on force to protect the boundaries of people within it—otherwise it’s not a world of freedom, but of might-makes-right. A lot of our civilization’s progress in governance mechanisms comes from improving the Pareto frontier of tradeoffs we can make between centralization and decentralization (I heard this point from Richard Ngo, in a talk that is unpublished as far as I know):

For example, democracy allows for centralizing more power in a government (reducing anarchy risk) without losing people’s ability to occasionally fire the government (reducing autocracy risk). Zero-knowledge proofs and memoryless AI allow verification of treaties or contracts (important for coordinating to solve risks) without any need to hand over information to some authority (which would centralize).

However, the tension remains. We want inviolable rights for individuals, but we also need some way to enforce those rights. Unless technology can make that fully decentralized (or David Friedman is right), that means we need at least some locus of central control, but this locus of course becomes the target of every seeker of power and rent. And remember, we want everything to be adaptable if circumstances change—but only for good reasons.

On a more fundamental level, everything being permitted is not necessarily a stable state. If, in free competition, there exist patterns of behavior that are better at gaining power than others, then you have to accept that those patterns will have a disproportionate share of future value. This leads to two concerns. First, as pointed out by Carlsmith in his talk “Can goodness compete?”, maximizing for goodness and maximizing for power are different concerns, so the optimum for one is likely not the optimum for the other. So in fully free competition, in this very simplified model, we lose on goodness. Secondly, if everything being permitted leads to competition in which some gain power until they are in a position to violate others’ boundaries, then full liberalism would bring about its own demise. It’s not a stable state.

Fifth, there’s a neutrality to liberalism. We give everyone their freedoms, we make everyone equal before the law—but what do we actually do? Whatever you want, that’s the point! And what do you want? Well, that’s your problem—we liberals just came here to set up the infrastructure, like the plumber comes to install your pipes. It’s your job to decide what runs through them, and to use them well.

Now, utilitarianism suffers from this problem too. What is utility? It’s what you like/prefer. But what are those things? Presumably, you’re supposed to just look inside you. But for what? Do you really know? The most hardcore hedonic utilitarians will claim it’s obvious: pleasure minus pain. But this is of course overly reductive, unless either you are a very simple person (lucky you—but what about the rest of us?) or you take a very expansive view of what pleasure and pain are (but then you’re back to the problem of defining them in a sufficiently expansive, yet precise, way).

Putting aside the abstract moral philosophies: in yet another essay, Carlsmith mentions the “Johnny Appleseeds” of the world:

Whatever your agricultural aspirations, he’s here to give you apple trees, and not because apple trees lead to objectively better farms. Rather, apple trees are just, as it were, his thing.

There’s something charming about this image. At the end of the day you need something worth fighting for. Everyone who has actually inspired people has not preached just an abstract set of rules, but has also breathed life into an entire worldview and way of life. Pure liberalism does not tell you what the content of life should be, it only says that in the pursuit of that content you should not take away other people’s freedoms to pursue theirs. At times you need the abstraction-spinning philosophers and even-handed policemen and hair-splitting lawyers to come and argue for and enforce the boundaries. But they are infrastructure, not content. The farmer told by the philosopher to believe in liberalism, or shown by the police and the lawyers where their plot ends and their neighbor’s begins, does not gain the content that animates a life. You also need a Johnny Appleseed, whether externally or within you, who preaches something specific, something concrete: look at this apple, feel its texture, smell its scent—this is what you should grow.

Much as there’s a distinction between the pipes as infrastructure and the water in the pipes, there’s a distinction between the structure of our moral system (or, to use a computer science metaphor, its type), and what we actually care about. What people really fight for is sometimes the abstract principle, but almost always there is something real and concrete too. But what exactly this is, and how different people find theirs, is subtle and complicated. The strength of liberalism is that it doesn’t claim an answer (remember: there is virtue to narrowness). Whatever those real and concrete actually-animating things are, they seem hard to label and put in a box. So instead: don’t try to specify them, don’t try to dictate them top-down, just lay down the infrastructure thats let people discover and find them on their own. In a word: freedom.

Weaving the rope

So how should we think about moral progress? A popular approach is to pick one tenet, such as freedom or utility, and declare it to be the One True Value. Everything else is good to the extent that it reflects that value, and bad to the extent it violates it. You can come up with very good stories of this form, because words are slippery and humans are very good at spinning persuasive stories—didn’t the Greeks get their start in philosophy with takes like “everything is water” or “everything is change”? If there are annoying edge cases—trolley problems for the utilitarians, anti-libertarian thought experiments for the liberalists—then you have to either swallow the bullets or try to dodge them as best as you can while. But all the while you gain the satisfaction that you’ve solved it, you’ve seen the light, the ambiguity is gone (or, at least in principle, could one day be gone if only we carry out some known process long enough)—because you know the One True Value.

But, as Isaiah Berlin wrote:

One belief, more than any other, is responsible for the slaughter of individuals on the altars of the great historical ideals [...]. This is the belief that somewhere, in the past or in the future, in divine revelation or in the mind of an individual thinker, in the pronouncements of history or science, or in the simple heart of an uncorrupted good man, there is a final solution.

An alternative image to the One True Value is making a rope. While it’s being plied, the threads of the rope are laid out on the table as the rope is being made, pointing in different directions, not yet plied into a single rope. The liberal idea of boundaries and rights is one thread, and it’ll go somewhere into the finished thing, as will the thread of utilitarian welfare, and others as well. We’ve knit parts of this rope already; witness thinkers from the Enlightenment philosophers onwards making lots of progress plying together freedom and welfare and fairness and other things, in ways that (say) medieval Europeans probably couldn’t have imagined. How do we continue making progress? Rather than declaring one thread the correct one for all time, I think the good path forwards looks more like continuing to weave together different threads and moral intuitions. I expect where we end up to have at least some depend on the path we take. I expect progress to be halting and uncertain; I expect sometimes we might need to unweave the last few turns. I expect eventually where we end up might look weird to us, much as modernity would look weird to medieval people. But I probably trust this process, at least if it’s protected from censorship, extremism, and non-human influences. I trust it more than I trust the results of a thought experiment, or any one-pager on the correct ideology. I certainly trust it far more than I trust the results of a committee of philosophers, or AI lab ethics board, or inhuman AI, to figure it out and then lock it in forever.

I hope you share the intuition above, and that the intuition alone is compelling. But can we support it? Is there a deeper reason why should we expect morality to work like that, and be hard to synthesize into exactly one shape?

The first reason to think this is that, empirically, human values just seem to be subtle and nuanced. Does the nature of the good seem simple to you? Could you design a utopia you felt comfortable locking in for all eternity? Hell is simple and cruel, while heaven is devious and subtle.

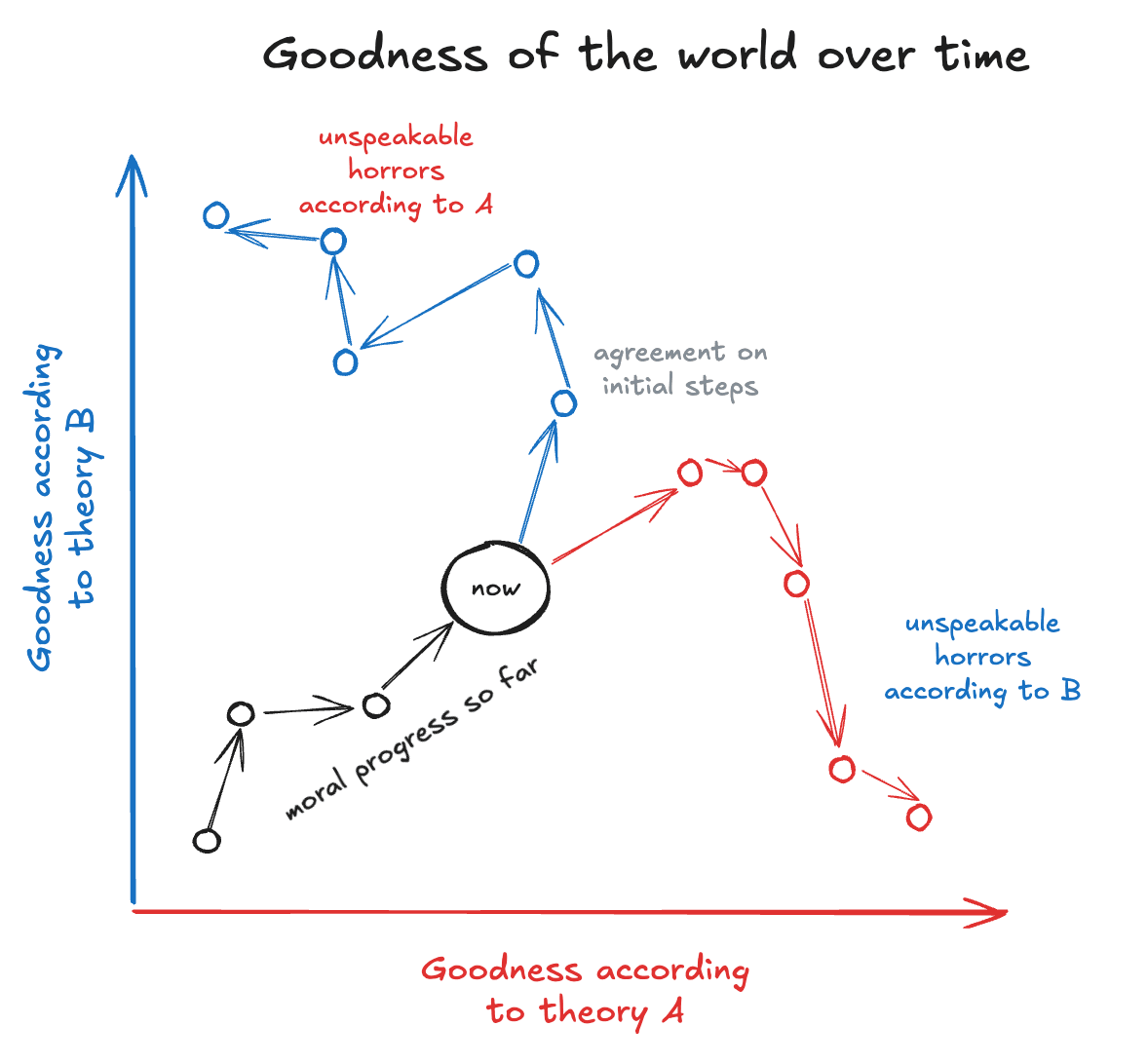

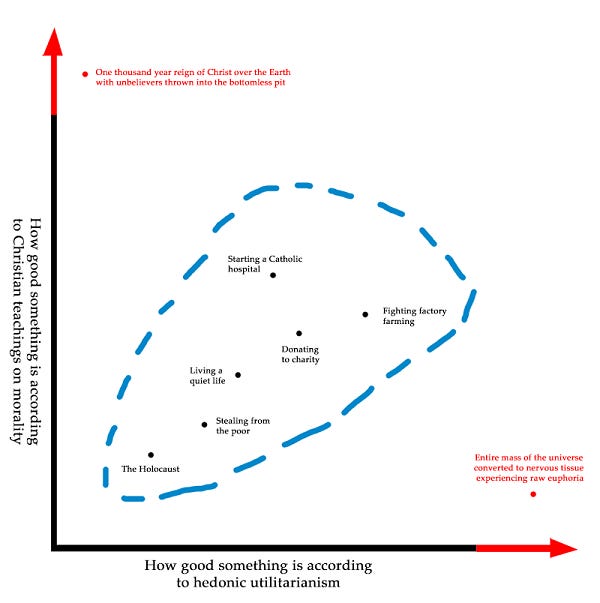

A second reason is that over-optimization is treacherous. This is the same instinct that leads Yudkowsky to think the totalizing AIs will rip apart all of us, and that leads Carlsmith to spend so many words poking at whether there’s something nicer and less-treacherous if only we’re more liberal, more “green” (in his particular sense of the word), nicer. Paul Christiano, one of the most prominent thinkers in AI alignment and an inventor of RLHF, centers his depiction of AI risk on “getting what you measure” all too well. But why? Goodhart’s law is one idea: over-optimize any measure, and the measure stops being a good measure. Another way to put this is that even if two things are correlated across a normal range of values, they decorrelate—the “tails come apart”—at extreme values, as LessWrong user Thrasymachus (presumably a different person from the ancient philosopher) observed and Scott Alexander expanded on. In the case of morality, for example:

Within the range of normal events, moral theories align on what is good. When it comes to abnormal events—especially abnormal events derived from taking one moral theory’s view of what is good and cranking everything to eleven—the theories disagree. The Catholic Church and the hedonic utilitarians both want to help the poor, but the utilitarians are significantly less enthusiastic about various Catholic limits on sexuality, and the Catholics are significantly less enthusiastic about everything between here and Andromeda converting to an orgiastic mass of brain tissue.

So if our choice is about which ideal we let optimize the world, and if that optimization is strong enough, we run a real risk of causing unspeakable horrors by the lights of other ideals regardless of which ideal we pick:

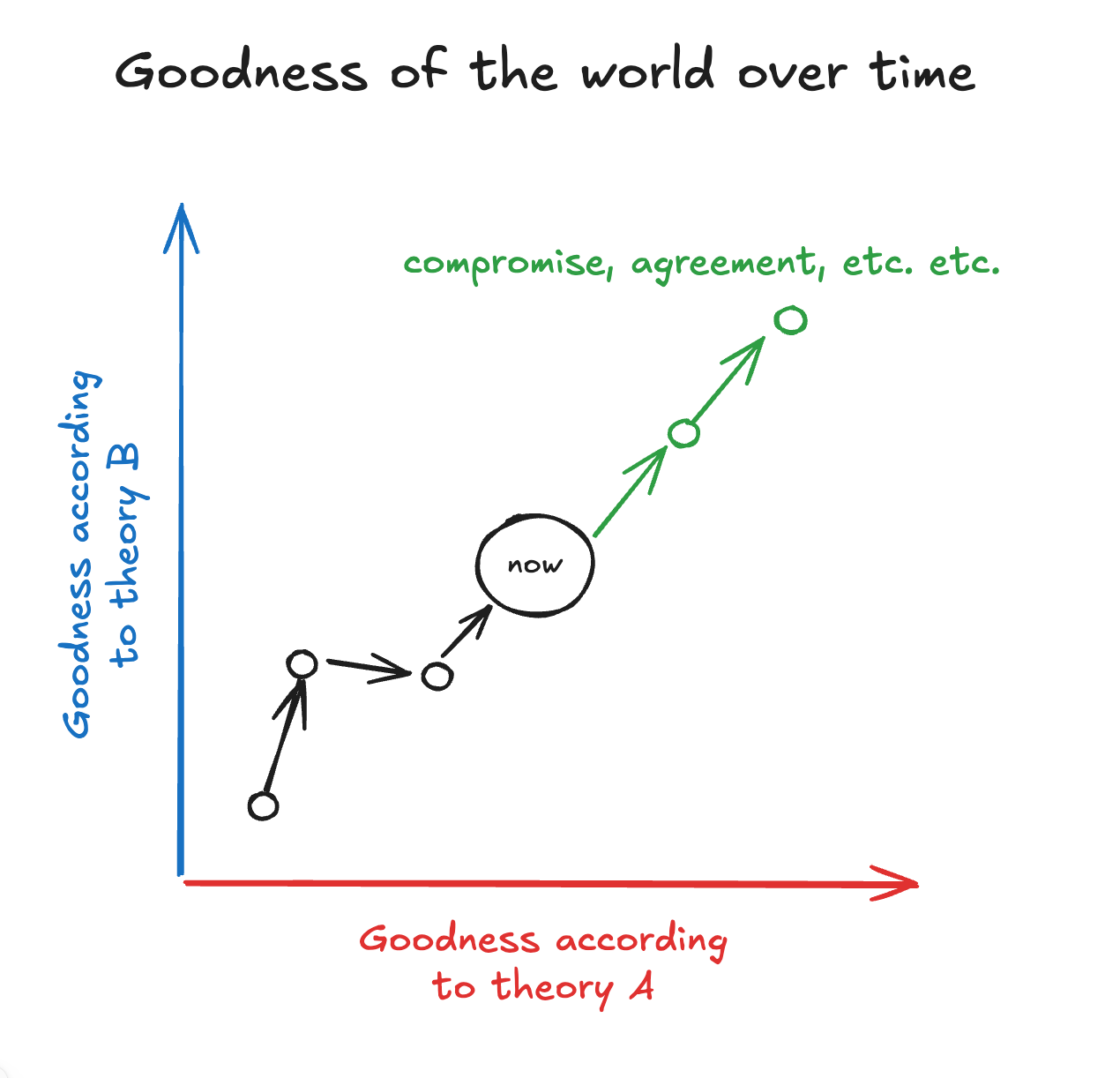

You might think what we want, then, is compromise. A middle path:

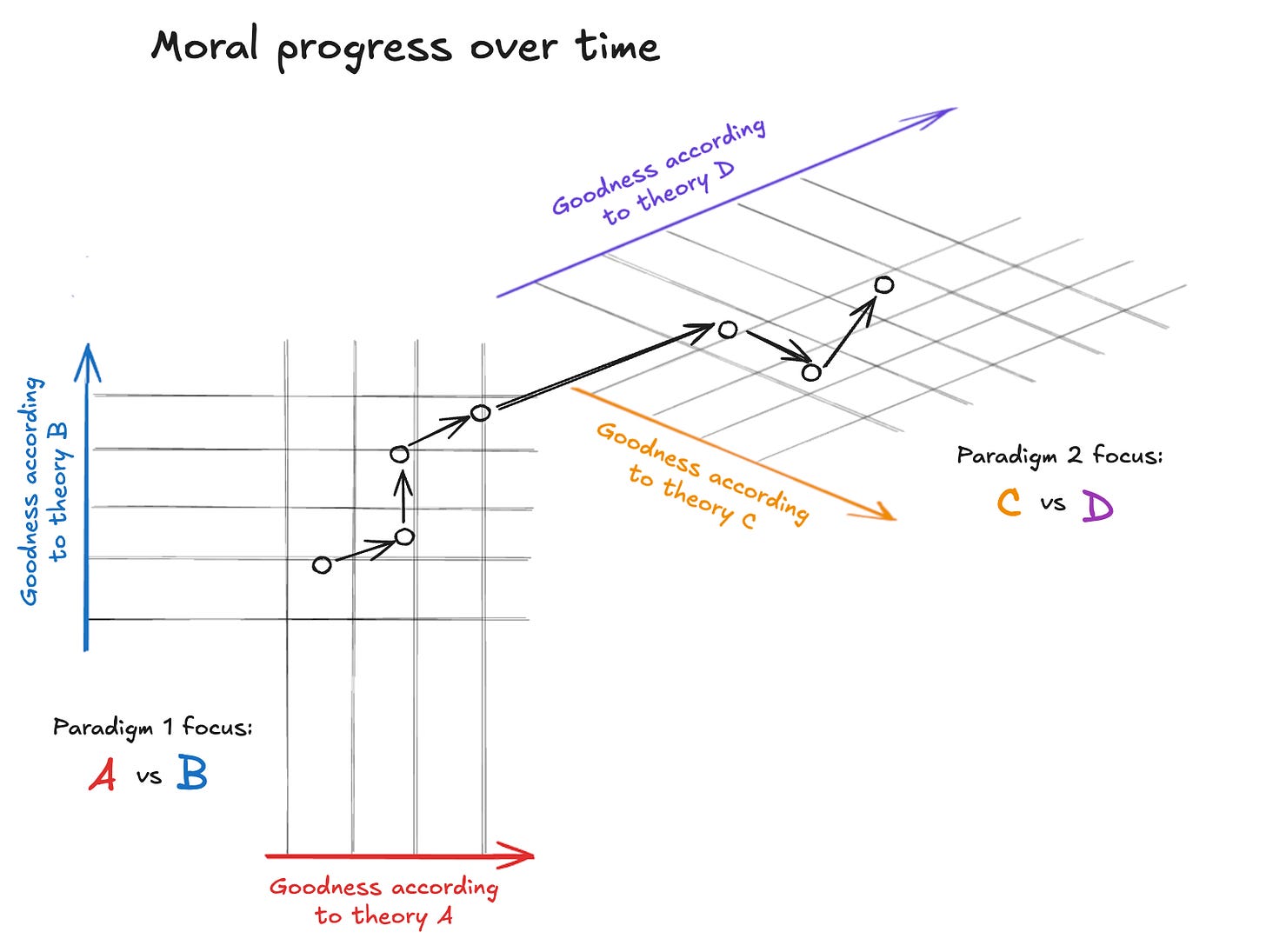

And yes, I expect a compromise would be better. But I think the above is reductive and simplistic. Whatever Theory A & Theory B are, they’re both likely static, contingent paradigms. Any good progress probably looks more like striking a balance than picking just one view of the good to maximize, but the most significant progress likely reframes the axes:

Different times and places argued about different axes: salvation versus worldliness, honor versus piety, or duties to family versus duties to the state. Liberalism versus utilitarianism, the framing of this post, is a modern axis. Or, to take another important modern axis: economic efficiency versus fairness of distribution. You need modern economics to understand what these things really are or why they might be at odds, it’s contingent on facts about the world including the distribution of economically-relevant talent in the population, and their importance rests on modern ethical ideas about the responsibilities of society towards the poor.

As mentioned before, to the extent that liberalism has any unique claim, it’s that it’s a good meta-level value system. Live and let live is an excellent rule, if you want to foster the continued weaving of the moral thread, including its non-liberal elements. It lets the process continue, and it lets the new ideas and new paradigms come to light and prove their worth. It seems far less likely to sweep away the goodness and humanity of the world than any totalizing optimization process aiming for a fixed vision of the good.

Isaiah Berlin, again:

For every rationalist metaphysician, from Plato to the last disciples of Hegel or Marx, this abandonment of the notion of a final harmony in which all riddles are solved, all contradictions reconciled, is a piece of crude empiricism, abdication before brute facts, intolerable bankruptcy of reason before things as they are, failure to explain and to justify [...]. But [...] the ordinary resources of empirical observation and ordinary human knowledge [...] give us no warrant for supposing [...] that all good things, or all bad things for that matter, are reconcilable with each other. The world that we encounter in ordinary experience is one in which we are faced with choices between ends equally ultimate, and claims equally absolute, the realization of some of which must inevitably involve the sacrifice of others. Indeed, it is because this is their situation that men place such immense value upon the freedom to choose; for if they had assurance that in some perfect state, realizable by men on earth, no ends pursued by them would ever be in conflict, the necessity and agony of choice would disappear, and with it the central importance of the freedom to choose. Any method of bringing this final state nearer would then seem fully justified, no matter how much freedom were sacrificed to forward its advance.

Luxury space communism or annihilation?

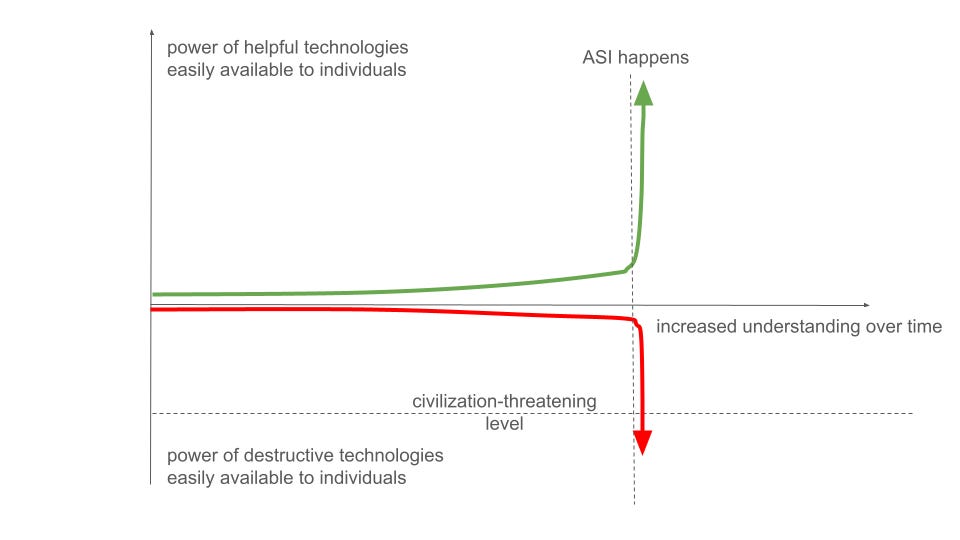

There’s a common refrain that goes something like this: over time, we develop increasingly powerful technology. We should aim to become wiser about using technology faster than the technology gives us the power to wreak horrors. The grand arc of human history is a race between available destructive power and the amount of governance we have. Competition, pluralism, and a big dose of anarchy might’ve been a fine and productive way for the world to be in the 1700s, but after the invention of either the Gattling gun, the atomic bomb, or AGI, we’ll have to grow up and figure out something more controlled. The moral arc of the universe might bend slowly, but it bends towards either luxury space communism or annihilation.

For an extended discussion of this, see Michael Nielsen’s essay on How to be a wise optimist about science and technology (note that while Nielsen is sympathetic to the above argument, he does not explicitly endorse it). In graph form (taken from the same essay):

Often, this then leads to calls for centralization, from Oppenheimer advocating for world government in response to the atomic bomb, to Nick Bostrom’s proposal that comprehensive surveillance and totalitarian world government might be required to prevent existential risk from destructive future technologies.

A core motivation of this line of reasoning is that technology can only ramp up the power level, the variance in outcomes, the destruction. This has generally been a net effect of technological progress. But there are other consequences of technology as well.

Most obviously, there are technologies that tamp down on the negative shocks we’re subject to. Vaccines are perhaps the most important example of technology against natural threats. But the things in the world that change quickly are the human-made ones, so what matters is whether we can build technologies that can tamp negative shocks from human actions (vaccines work against engineered pandemics as well!). If all we have for defense is a stone fence, this isn’t too bad if the most powerful offense was a stone axe. But now that we’ve built nuclear weapons, can we build defensive fences strong enough?

Also: there are technologies that aren’t about offense/defense balance that make it easier or harder to enforce boundaries. Now we have cryptography that lets us keep information private, but what if in the future we get quantum computers that break existing cryptography? In the past it was hard to censor, but now LLMs make censorship trivially cheap. And consider too that what matters is not just capabilities, but propensity. Modern nuclear states could kill millions of people easily, but they’re prevented from doing so by mutually assured destruction, international norms, and the fact that nuclear states benefit from the world having lots of people in it engaging in positive-sum trade. Offense/defense balance is not the only axis.

Differential acceleration of defensive technology is something that Vitalik Buterin has argued for as part of his “d/acc” thesis. However, for reasons like the above, he deliberately keeps the “d” ambiguous: “defense”, yes, but also “decentralization” and “democracy”.

Is d/acc just a cluster of all the good things? With the liberalism v utilitarianism axis, I think we can restate an argument for d/acc like this: a lot of technology can be used well for utilitarian ends, in the sense that it gives us power over nature and the ability to shape the world to our desires, or to maximize whatever number we’ve set as our goal: make the atoms dance how we want. But this also increases raw power and capabilities, and importantly creates the power for some people—or AIs—to make some atoms you care about dance in a way you don’t like.

Now, if you think that unlimited raw power is coming down the technological pipeline, say in the form of self-improving AIs that might build a Dyson sphere around the sun by 2040, your bottleneck for human flourishing is not going to be raw power or wealth available, or raw ability to shape the world when it’s useful, or raw intelligence. It’s likely to be much more about enforcing boundaries, containing that raw power, keeping individual humans empowered and safe next to the supernova of that technological power.

So what we also need are technologies of liberalism, that help maintain different spheres of freedom, even as technologies of utilitarianism increase the control and power that actors have to achieve their chosen ends.

Technologies of liberalism

Defense, obviously, is one approach: tools that let you build walls that keep in things you don’t want to share, or lock out things you don’t like.

Often what’s important is selective permeability. At the most basic level, locks and keys (in existence since at least ancient Assyria 6000 years ago) let you restrict access to a place. Today, the ability to pass information over public channels without revealing it is at least as fundamental to our world as physical locks and keys. Also note how unexpected public key cryptography—where you don’t need to first share a secret with the counterparty—is. Diffie-Helman key exchange is one of the cleverest and most useful ideas humans have ever had.

Encryption is of enormous significance for the politics of freedom. David Friedman has argued (since the 1990s!):

In the centuries since [the passing of the Second Amendment], both the relative size of the military and the gap between military and civilian weapons have greatly increased, making that solution less workable [for giving citizens a last resort against despotic government]. In my view, at least, conflicts between our government and its citizens in the immediate future will depend more on control of information than control of weapons, making unregulated encryption [...] the modern equivalent of the 2nd Amendment.

Ivan Vendrov, in a poetic essay on the building blocks of 21st century political structure, points to cryptography (exemplified by the hash function) as the one thing standing against the centralizing information flows that incentivizes, since it lets us cheaply erect barriers that have astronomical asymmetry in favor of defense. Encryption that takes almost no time at all can be made so strong it would take hundreds of years on a supercomputer to break. In our brute physical world, destruction is easy and defensive barriers are hard. But the more of our world becomes virtual, the more of our society exists in a realm where defense is vastly favored. Of the gifts to liberty that this universe contains that will most bear fruit in our future, encryption ranks along the Hayekian nature of knowledge and the finite speed of light.

So far we are far from realizing the theoretical security properties of virtual space; reliable AI coding agents and formal verification will help. And virtual space will continue being embedded in meatspace.

In meatspace, the biggest vulnerability humans have are infectious diseases. The state of humanity’s readiness against pandemics (natural or engineered) is pathetic, and in expectations millions and more will pay with their lives for this. We need technology that lets us prevent airborne diseases, to prevent an increasing number of actors—already every major government, but soon plausibly any competent terrorist cell—wielding a veto on our lives. UV-C lighting and rapid at-home vaccine manufacturing are good starts. Also, unless we curtail this risk through broad-spectrum defensive technology, at some point it will be used as an excuse for massive centralization of power to crush the risk before it happens.

Besides literal defenses, there’s decentralization: self-sufficiency gives independence as well as safety from coercion. At a simple level, solar panels and home batteries can help with energy independence. 3D printers make it possible to manufacture more locally and more under your control. Open-source software makes it possible for you to tinker with and improve the programs you run. AI code-gen makes this even stronger: eventually, anyone will be able to build their own tech stack, rather than being funneled along the grooves cut by big tech companies—which, remember, they adversarially optimize against you to make you lose as much time out of your life as possible. The printing press and the internet both made it cheaper to distribute writing of your choice, and hence push your own ideas and create an intellectual sphere of your own without wealth or institutional buy in.

Fundamentally, however, the thing you want to do is avoid coercion, rather than maximize independence. No man is an island, they say, and that might not have been intended as a challenge. Coercion is hard if the world is very decentralized, to the point that no one has a much larger power base than anyone else. However, such egalitarianism is unlikely since everyone has different resources and talents. Another key feature of the modern world that helps reduce coercion, in addition to economic and military power being decentralized, is that the world is covered in a thick web of mutual dependence thanks to trade. If you depend on someone, you are also unlikely to be too coercive towards them, as Kipling already understood. Self-sufficiency and webs of mutual dependencies are, of course, in tension. I don’t pretend there’s a simple way to pick between them, or know how much of each to have—I never said this would be simple!

AI, however, is a challenge to any type of decentralization: it needs lots of expensive centralized infrastructure, and currently the focus is on huge multi-billion dollar pre-training runs. However, even here there’s a story for something more decentralized to take center stage. First, zero-trust privacy infrastructure for private AI inference & training—salvation by cryptography once again!—can give you verifiable control and privacy over your own AI, even if it runs in public clouds for cost reasons. Secondly, as Luke and I have argued, the data needs to have AI diffuse through the economy run into Hayekian constraints that privilege the tacit, process, and local knowledge of the people currently doing the jobs AI seeks to replace—as long as the big labs and their data collection efforts don’t succeed too hard and too fast. Combined with this, cheap bespoke post-training offers a Cambrian explosion of model variety as an alternative to the cultural & value lock-in to the tastes of a few labs. Achieving this liberal vision of the post-AGI economy is what we’re working on at Workshop Labs.

Then there’s technology that helps improve institutions—democratization, but not “democracy” as in just “one person one vote”, but in the more fundamental sense of “people” (the demos) having “power” (kratos). We’ve already mentioned zero-knowledge proofs, memoryless AI, and other primitives for contracts. Blockchains, though much hyped, deserve some space on this list, since they let you get hard-to-forge consensus about some data without a central authority (needing consensus about a list is a surprisingly common reason to have a central authority!). More ambitiously, Seb Krier points out AI could enable “Coasean bargaining” (i.e. bargaining with transaction costs so low Coase’s theorem actually holds)—bespoke deals, mediated by AIs acting on behalf of humans, for all sorts of issues that currently get ignored or stuck in horrible equilibria because negotiating requires expensive human time. Another way to increase the amount of democracy when human time is bottlenecked is AI representatives for people (though these would have to be very high-fidelity representatives to represent someone’s values faithfully—values are thick, not thin, and AI design should take this into account).

Finally, there are technologies shape culture and make us wiser, or let society be more pluralistic. Many information technologies, like the internet or AI chatbots, obviously fall in this category and enable great things. However, information technology, in addition to giving us information and helping us coordinate, often also changes the incentives for which memes (in the original Dawkins sense) spread, and therefore often have vast second-order consequences. On net I expect information technology to be good, but with far more requirements for cultural shifts to properly adapt to them, and far more propensity than other technologies to shift culture or politics in unexpected directions.

(Note that the pillars above are very similar to the those of the anti-intelligence-curse strategy Luke & I outlined here.)

Historically, you can trace the ebb and flow of the plight of the average person by how decentralizing or centralizing the technology most essential for national power is, and how much that technology creates mutual dependencies that make it hard for the elite to defect against the masses. MacInnes et al.’s excellent paper Anarchy as Architect traces this back throughout history. Bronze weapons, which required rare bronze, meant only a small military elite was relevant in battle, and could easily rule over the rest. The introduction of iron weapons, which could be produced en-massed, lead to less-centralized societies, as the rulers needed large groups to fight for them. Mounted armored knights centralized power again, before mass-produced firearms made large armies important again. The institutions of modern Western democracy were mostly built during the firearm-dominated era of mass warfare. They were also built at a time when national power relied more and more on broad-based economic and technological progress where a rich and skilled citizenry was very valuable. This rich and skilled citizenry was also increasingly socially mobile and free of class boundaries, making it harder for the upper class to coordinate around its interests since it wasn’t demarcated by a sharp line. People also had unprecedented ability to communicate with each other in order to organize and argue thanks to new technology (and, of course, because the government now had to teach them to read—before around 1900, literacy was not near-universal even in rich countries). These nations then increasingly dissolved trade barriers between them and became interdependent—very purposefully and consciously, in the case of post-war Europe—which reduced nation-on-nation violence and coercion.

How will this story continue? It will definitely change—as it should. We should not assume that the future socio-structural recipe for liberalism is necessarily the one it is now. But hopefully it changes in ways where it still adds up to freedom for an increasing number.

Build for freedom

Differential technological progress is obviously possible. For example, Luke argues against what he calls “Technocalvinism“, the belief that the “tech tree” is deterministic and everything about it is preordained, using examples ranging from differential progress in solar panels to the feasibility of llama-drawn carts. The course of the technology is like a new river running down across the landscape. It has a lot of momentum, but it can be diverted from one path to another, sometimes by just digging a small ditch.

There are three factors that help, the first two in general, and the last specifically for technologies of liberalism:

There is a lot of path dependence in the development of technologies, and effects like Wright’s law mean that things can snowball: if you manage to produce a bit, it gets cheaper and it’s better to produce a larger amount, and then an enormous amount. This is how solar panels went from expensive things stuck on satellites to on track to dominate the global energy supply. Tech, once it exists, is also often sticky and hard to roll back. A trickle you start can become a stream. (And whether or not you can change the final destination, you can definitely change the order, and that’s often what you need to avert risks. All rivers end in the ocean, but they take different paths, and the path matters a lot for whether people get flooded.)

The choice of technology that a society builds towards is a deeply cultural, hyperstitious phenomenon. This is argued, for example, by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber’s Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation (you can find an excellent review here, which occasionally even mentions the book in question). The Apollo program, the Manhattan project, or the computer revolution were all deeply idealistic and contingent projects that were unrealistic when conceived—yes, even the computer revolution, hard as it is to remember today. Those who preach the inevitability of centralization and control, whether under the machine-god or otherwise, are not neutral bullet-biters, but accidentally or intentionally hyperstitioning that very vision into life.

Demand is high. People want to be safe! People want control! People want power!

So how should we steer the river of technology?

If the AGI labs’ visions of AGI is achieved, by default it will disempower the vast majority of humanity instantly, depriving them of their power, leverage, and income as they’re outcompeted by AIs, while wrecking the incentives that have made power increasingly care about people over the past few centuries, and elevating a select few political & lab leaders to positions of near godhood. It might be the most radical swing in the balance of power away from humanity at large and towards a small elite in human history. And the default solution for this in modern AI discourse is to accept the inevitability of the machine-god dictatorship, accept the lock-in of our particular society and values, and argue instead about who exactly stands at its helm and which exact utility function is enshrined as humanity’s goal from here on out.

All this is happening while liberalism is already in cultural, political, and geopolitical retreat. If its flame isn’t fanned by the ideological conviction of those in power or the drift of geopolitics, its survival increasingly depends on other sources.

So: to make an impact, don’t build to maximize intelligence or power, because this will not be the constraint on a good future. This is a weird position to be in! Historically, we did lack force and brains, and had to claw ourselves out of a deep abyss of feebleness to our current world of engines, nuclear power, computers, and coding AIs. Even now, if radical AI was not an event horizon towards which we were barreling towards that was poised to massively accelerate technology and reshape the position of humans, more power would be a very reasonable thing to aim towards—we would greatly benefit from energy abundance thanks to fusion, and robotics beyond our dreams, and space colonization. (And if that radical AI looks majorly delayed, or gets banned, or technology in general grinds to a halt, then making progress towards tools of utilitarianism and power would once again be top-of-mind.) But if radical tech acceleration through AI is on the horizon, we might really be on track for literally dismantling the solar system within the few decades. The thing we might lack is the tools to secure our freedoms and rights through the upheaval that brings. Technologists, especially in the Bay Area, should rekindle the belief in freedom that guided their predecessors.

For decades, the world has mostly been at peace, liberty has spread, and the incentives of power have been aligned with the prosperity of the majority. History seemed over. All we had to do was optimize our control and power over nature to allow ever greater and greater welfare.

But now, history is back. Freedom is on trial. The technology we choose to build could tip the scales. What will you build?

Thank you to Luke Drago & Elsie Jang for reviewing drafts of this post.